“Man was matter, that was Snowden’s secret.” ―Joseph Heller, Catch-22

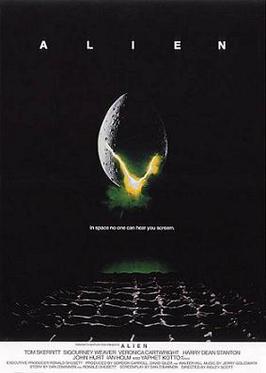

Much has been written already about Ridley Scott’s 1982 film Blade Runner (my original choice) in relation to Donna Haraway’s landmark essay “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” but less about the essay’s relation to Scott’s first great film, Alien (1979). For this short essay I’d like to avoid the feminist jungle that Alien offers for analysis and instead focus on the characters of Ash and Kane.

Original movie poster from 1979

Ash is an android whose simulated nature is revealed halfway through the film. It seems a deliberate move to surprise us in this way, leaving the audience fooled on a deep and disturbing level, by a character whom we came to know as human and realized is only a system of wires that oozes blood the color of Cream of Wheat (not unlike the alien’s “acid” blood). The scene is a violent one, with a disagreement between Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and Ash turning physical. Ash unsuccessfully attempts to suffocate Ripley by stuffing a rolled up (phallic) magazine into her mouth, and it marks the only time in the film when a female is threatened in an overtly sexual way. The suggestion is that Ash is compensating for his lack of sexuality as an android, and although he is ostensibly “male” he more closely resembles what Haraway calls the “post-gender” world of the cyborg. But our heroine prevails, and quickly: Ripley decapitates Ash (who is literally reduced to a talking head, a system of code and information, without a body) and annihilates him in a bath of flame with a blowtorch.

Once this revelation about Ash happens, the “nature” of everyone else on the ship becomes suspect, and, further, we as viewers begin to question our own nature. How different are we from Ash’s robotic body with wires for guts? If androids are machines that can be terminated, what does that make us? Don’t we have the ability to end their “life” as God ends ours? The result of this scene is a blurring of the boundary between man (organism) and machine, and it anticipates Haraway’s essay, published six years later.

Donna Haraway in 1988

Yet Haraway’s is an argument “for pleasure in the confusion of boundaries,” and Alien represents the antithesis of this. In a film whose monster is heavily imbued with both phallic and vaginal imagery, a scene of “oral rape” in which a male character (Kane) is impregnated orally by an alien species, and another scene where the planted egg erupts violently from Kane’s chest, the deconstruction (and fusion) of gender and sexual boundaries is deliberately horrifying, not pleasurable.

I would argue that upon viewing the film a second time, one of the most subtly disorienting scenes is the moment just before the alien erupts from the character Kane’s chest, when the crew is casually sitting around eating breakfast, and we realize that Kane is pregnant. Though the pregnancy is short-lived, he is ultra-feminized in a sense, and the result is a viciously violent one that kills him. The suggestion, then, is that the attempt to transgress gender by fusing its boundaries, especially in a sexual way, is highly volatile. As Haraway says, “To be feminized means to be made extremely vulnerable…exploited as a reserve labor force.” Kane is raped and exploited by being used as a vessel out of which the alien egg can hatch. He is not emasculated so much as violently feminized, and I would argue that the result of this is a radical re-feminization of the film’s hero, Ripley.

The film consciously raises our anxieties and fears surrounding the issue of playing God, and losing our assumed boundaries of male and female, but also of the Self and the Other. The characters of Kane and Ash question our historical idea of the body and its permeable nature, and remind us that “man is matter,” capable of being mutated, exploited, simulated, and impregnated. Haraway’s dominant-submissive dualism speaks to women primarily, and Alien represents a reversal of that domination, not without its casualties.