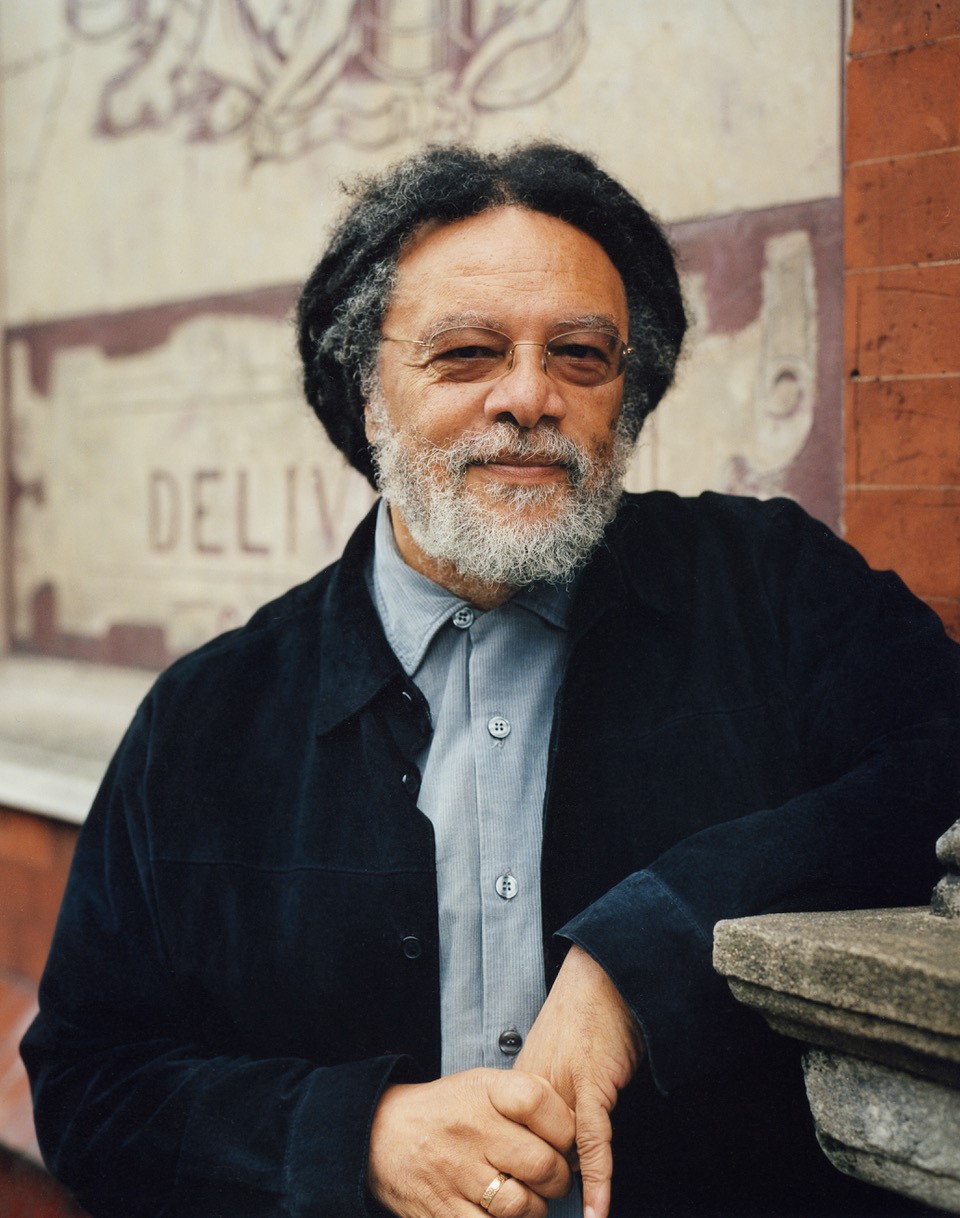

While reading Bessel van der Kolk’s remarkable book about trauma, The Body Keeps the Score, I was struck by the ubiquity of the word “frozen” and suddenly it reminded me of one of my favorite quotes from one of my favorite writers, Franz Kafka, where he states that “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.” It occurred to me that if we apply what Van der Kolk has discovered about the nature of trauma, which he details thoroughly in Body, we can understand on a deeply personal level what Kafka’s quote may have meant for him, and in turn what it can mean for us.

This is an excerpt from Kafka’s “Letter to His Father,” published in its entirety in various editions:

There is only one episode in the early years of which I have a direct memory. You may remember it, too. One night I kept on whimpering for water, not, I am certain, because I was thirsty, but probably partly to be annoying, partly to amuse myself. After several vigorous threats had failed to have any effect, you took me out of bed, carried me out onto the balcony, and left me there alone for a while in my nightshirt, outside the shut door. I am not going to say that this was wrong—perhaps there was really no other way of getting peace and quiet that night—but I mention it as typical of your methods of bringing up a child and their effect on me. I dare say I was quite obedient afterward at that period, but it did me inner harm. What was for me a matter of course, that senseless asking for water, and then the extraordinary terror of being carried outside were two things that I, my nature being what it was, could never properly connect with each other. Even years afterward I suffered from the tormenting fancy that the huge man, my father, the ultimate authority, would come almost for no reason at all and take me out of bed in the night and carry me out onto the balcony, and that consequently I meant absolutely nothing as far as he was concerned.

Kafka’s father never read the letter. He states that his father left him out there for “a while,” so we don’t know for how long, or how he eventually re-entered the house. Did his father let him back in? I’m very curious about that part of the incident, but regardless, the effect was one of “inner harm” as stated by Kafka. What he refers to as “inner harm,” we now refer to as trauma.

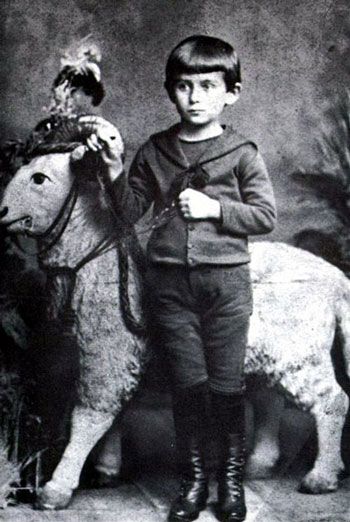

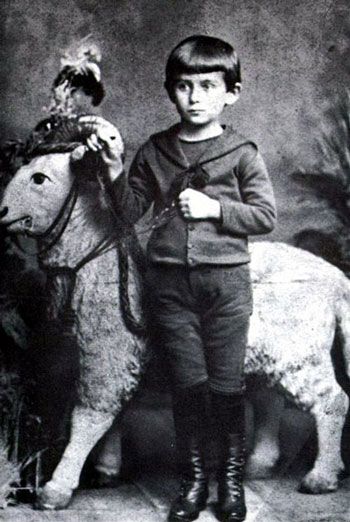

Kafka as a Boy, c. 1888

This episode, and Kafka’s recollection of it, is significant on a number of levels. Primarily it details a trauma which undoubtedly left a deep impression on the writer and greatly influenced his work. Van der Kolk describes how, in the midst of trauma, sometimes our fight-or-flight instinct is stilted, and we go into a third mode, which is to freeze. One can picture little Kafka on the balcony, quite literally freezing in his nightshirt, but without anywhere to flee to for warmth, and without being able to re-enter his house to confront his father. The word “frozen,” then, has a dual meaning in this context. For Kafka he was both immobilized and shivering cold. When we speak of water that has frozen into ice it is to say that the movement of the molecules within has ceased. For Kafka, the only way out of this paralysis was through his writing.

The PTSD that we used to think only applied to war veterans very much applies to any person with unresolved trauma, and whose body holds its lasting effects over time. Van der Kolk details what happens physiologically when a person is immobilized during a threat:

When the brain’s alarm system is turned on, it automatically triggers preprogrammed physical escape plans in the oldest parts of the brain. As in other animals, the nerves and chemicals that make up our basic brain structure have a direct connection with our body. When the old brain takes over, it partially shuts down the higher brain, our conscious mind, and propels the body to run, hide, fight, or, on occasion, freeze (italics mine). By the time we are fully aware of our situation, our body may already be on the move. If the fight/flight/freeze response is successful and we escape the danger, we recover our internal equilibrium and gradually “regain our senses.”

A “successful” use of freezing would be if Kafka’s father, in a fury, came looking for him, but could not find him, because Kafka was hiding, purposely immobilized, and therefore undetected. That is not the case here. The survival mechanisms normally at his disposal were all useless in this situation: there was no one to fight, nowhere to hide, and nowhere to run. When these options are not available, the brain continues to secrete stress hormones, like cortisol, and equilibrium is not restored. The trauma, then, stays “trapped” in the body in a very real way, and “long after the actual event has passed, the brain may keep sending signals to the body to escape a threat that no longer exists.” I believe this episode was a major traumatic incident that came to inhabit Kafka’s body and mind, and manifested itself throughout his writing.

We can see this “learned helplessness,” as Van der Kolk calls it, throughout Kafka’s works, and none better than his most popular and enduring work, The Metamorphosis, which opens with our antihero Gregor having been turned into a kind of beetle and struggling to move. So much of Metamorphosis involves Gregor struggling with the predicament of his own body. The entire first part of the story involves Gregor simply trying to figure out how to get out of bed. The genius of Metamorphosis is the way it fully expresses the unavoidable human problem of the body by dehumanizing its main character. For Gregor, mobility has been lost because his mind and his body are at odds with each other.

Kafka’s parable speaks to what it means to be human and to be inside a body, to have a body, but on a more personal level it speaks to the paralysis of lingering trauma that began the night he was stranded on the balcony. It is the body, then, that Gregor (and Kafka himself) struggle with, and the reason is because it has become paralyzed by unresolved trauma, and therefore its owner has lost the agency to move about freely.

If trauma is the thing that left Kafka paralyzed, shame is what forced him to hide what he had become. In Van der Kolk’s terms, the body becomes “stuck in fight or flight,” and the result is that it can do neither. Over time, “shame becomes the dominant emotion [for trauma survivors] and hiding the truth the central preoccupation.”

Indeed, throughout the entire Metamorphosis, Gregor barely makes it past the boundary of his room, which is the boundary of his internalized trauma-turned-shame, except briefly in one extraordinary episode that I believe to be one of the most powerful in all of literature. In this scene, Gregor’s sister is playing the violin for a trio of lodgers who have come to rent out the guest room in the home. Much has been written about this scene, but not in the context of trauma. Consider the following lines, which, in Kafka’s quintessential objective tone, seem unremarkable at first:

Gregor’s sister began to play; the father and mother, from either side, intently watched the movements of her hands. Gregor, attracted by the playing, ventured to move forward a little until his head was actually inside the living room. He felt hardly any surprise at his growing lack of consideration for others; there had been a time when he prided himself on being considerate. And yet just on this occasion he had more reason than ever to hide himself, since owing to the amount of dust which lay thick in his room and rose into the air at the slightest movement, he too was covered with dust, fluff and hair and remnants of food trailed with him caught on his back and along his sides; his indifference to everything was much too great for him to turn on his back and scrape himself clean on the carpet, as once he had done several times a day. And in spite of his condition, no shame deterred him from advancing a little over the spotless floor of the living room. [italics mine]

Spanish ed. of Metamorphosis from 1986

It is in this episode, and only in this episode, that Gregor attempts to move through the paralysis of his internalized trauma, by overcoming the debilitating and confining boundary of shame, marked by the line which delineates his room from the living room. His shame is illustrated here by the dirtiness of the local debris which has accumulated onto his body since the morning of his transformation, a debris which he has unsuccessfully tried to rid himself of permanently. The debris has been caked on to Gregor’s body, an important detail that speaks to how shame attaches itself in a very physical way to the body, immobilizing its victim. We can see this as well in one of Kafka’s dreams involving his father, as he describes it in his Diaries, approaching a gate, on the other side of which is a wall, which his father climbs “almost in a dance” but does not help his son ascend:

I got to the top only with the utmost effort, on all fours, often sliding back again, as though the wall had become steeper under me. At the same time it was also distressing that it was covered with human excrement so that flakes of it clung to me, chiefly to my breast. I looked down at the flakes with bowed head and ran my hand over them. When at last I reached the top, my father…immediately fell on my neck and kissed an embraced me.

Consider how the dream morphs Kafka into an animal (“on all fours”), requires a Herculean effort, given the steepness and slippery quality of the wall, leaves his father on the other side of the wall without a helping hand, and presents the internalized shame as excrement attaching itself to his body and making it difficult to move upward. The intimacy with which Kafka runs his hand over the flakes of excrement suggests that he has accepted, rather than rejected, this deep internalized shame. Excrement is the perfect metaphor for internalized shame because it is produced inside the body, invisible to us, and yet must be rid of or it will become a kind of poison. In Vladimir Nabokov’s reading of Metamorphosis, he suggests that the insect Gregor has transformed into is specifically a dung beetle, which I believe to be perfectly on point.

The crucial part of this dream, however, is the victory it represents, the kind of which we do not ever see in Kafka’s writing. It is a classic wish-fulfilment dream, where Kafka successfully traverses the wall of shame separating him from his father, thus earning his father’s love and affection once again. It is a reunion with the father after having been abandoned by the father.

In Metamorphosis, Gregor has been cut off from his family (yet so close to them at the same time, just a room away) exactly like he was that night on the balcony. Now he must set out to accomplish what Kafka accomplished in his dream: to reunite with his family. But can this be done? It is important to point out that a key part to what allows Gregor to begin this movement is not just the sound of his sister playing the violin, but his “lack of consideration” for others. This may seem strange, but it is precisely our ties to the people who have traumatized and shamed us that keep us immobile. Our deep fear of upsetting them, of being punished or shamed again, keeps us confined to ourselves and cut off from the people around us. Gregor displays a boldness here that allows him to disregard potential consequences and move towards the sounds of love, family, and community. He desperately needs to be a part of what is around him, rather than a prisoner in his own home. He also displays a courageous vulnerability, being that, covered in more filth than ever before, he has “more reason than ever to hide himself.” The scene continues as Gregor cautiously attempts to move out of the frozen place of shame and trauma, toward the desired goal of reuniting with his family. Consider the following words carefully in light of what we have discussed thus far:

Gregor crawled a little farther forward and lowered his head to the ground so that it might be possible for his eyes to meet hers. Was he an animal, that music had such an effect upon him? He felt as if the way were opening before him to the unknown nourishment he craved. He was determined to push forward till he reached his sister, to pull at her skirt and so let her know that she was to come into his room with her violin, for no one here appreciated her playing as he would appreciate it. He would never let her out of his room, at least, not so long as he lived; his frightful appearance would become, for the first time, useful to him; he would watch all the doors of his room at once and spit at intruders; but his sister should need no constraint, she should stay with him of her own free will; she should sit beside him on the sofa, bend down her ear to him and hear him confide that he had had the firm intention of sending her to the Conservatorium… After this confession his sister would be so touched that she would burst into tears, and Gregor would then raise himself to her shoulder and kiss her on the neck, which now that she went to business, she kept free of any ribbon or collar.

Here Gregor leaps into a detailed fantasy of his sister as rescuer, and the fantasy involves having a female companion (complete with incestual undertones) who accepts him, listens to him, and never abandons him. The fantasy represents all of Gregor’s deepest needs conflated, dream-like, into one perfect image. There is physical intimacy, emotional intimacy, and sexual intimacy all combined. All of his deepest needs (the “unknown nourishment” that he craves) could be met if only this fantasy might become a reality: family, companionship, love, affection, sexual expression—all from a single source. It is the ultimate fantasy, because it perfectly, and all at once, breaks the chains of the shame-based trauma in which he is shackled. It is the infantile wish to secure a source of nourishment that will never leave. Note, too, the detail of Gregor kissing Grete’s neck, just as Kafka’s father kissed his neck in his dream.

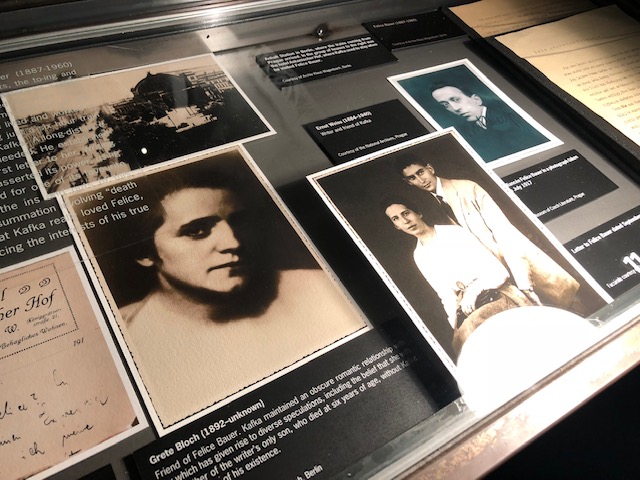

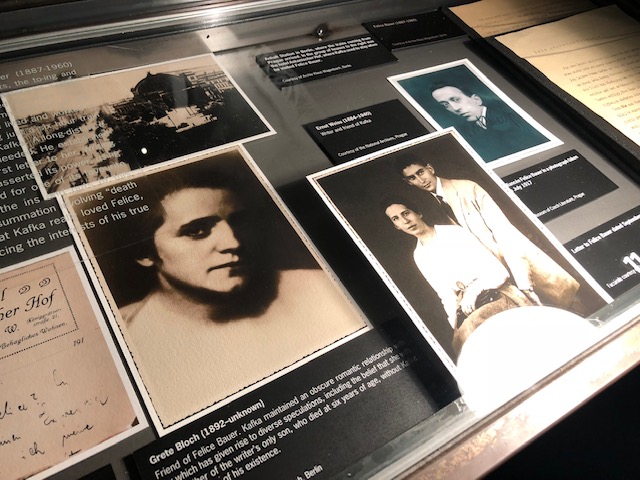

Photo of Grete Bloch, with whom Kafka had a romantic relationship, at the Kafka Museum, Prague.

Alas, the result of Gregor edging his way across the boundary of his own shame is disastrous, and his attempt only deepens his shame and re-traumatizes him. His father tries to calm the lodgers, who are alarmed by Gregor and disgusted, refusing to pay for their stay. Meanwhile Gregor’s movement has halted and he is paralyzed once again: “Disappointment at the failure of his plan, perhaps also the weakness arising from extreme hunger, made it impossible for him to move.” Contrary to his fantasy of being rescued by Grete, Gregor’s sister now insists that he must be got rid of, referring to him as “it” while addressing their parents. She no longer acknowledges his humanity. Gregor is simply garbage, filth, and this is the stark reality of the psyche that is imprisoned by toxic shame. The shame-based person believes himself to be worthless. In John Bradshaw’s book, Healing the Shame that Binds You, he explains toxic shame this way: “Toxic shame, the shame that binds us, is experienced as the all-pervasive sense that ‘I am flawed and defective as a human being…’ Toxic shame gives you a sense of worthlessness, a sense of failing and falling short as a human being… [and] creates a tormenting self-consciousness [that has] a ‘binding and paralyzing effect upon the self.’” And later, he addresses the consequences of shame internalization: “A shame-based identity is formed [and] the depth of shame is magnified and frozen.” [italics mine]

Kafka at age 40, just before his death

Of all the remarkable interpretations of Kafka’s masterpiece, in the end, The Metamorphosis is a story about the paralysis of shame. It becomes clear through our investigation of Kafka’s traumatic childhood incident (just one of many), of being abandoned by his father, cut off from his family, banished from the warmth and comfort of his home, that this trauma led to a deep shame that left Kafka internally paralyzed, his emotional self a “frozen sea” that he attempted, through the sheer will of his own genius, to break apart with the sharpened axe of his own writing.

But was he successful? Gregor does not emerge victorious the way Kafka himself did in his dream. For if he had, the story would have ended with the lodgers, Mr. and Mrs. Samsa, and (most importantly) Grete all receiving him with open arms in the living room, under the spell of Grete’s violin. They might have sung and danced, and embraced Gregor even in his ugliness. That would have been true acceptance, the mark of unconditional love. But Metamorphosis does not end in a reunion or with any intimacy. Instead, Gregor heartbreakingly turns round without a word, crawling back into the cell of his room, and at three in the morning, sinks his head Christ-like and dies. Upon hearing the news of his son’s death, Mr. Samsa says “Well, now thanks be to God.”

The tragedy of Metamorphosis is that it reinforces Kafka’s own shame by depicting a narrative in which he rids himself from his family, so that they experience relief by being rid of him, rather than one in which he reunites with his family by transcending the frozen inner self.

Kafka was not one for happy endings. However, we can benefit from this powerful story that, once read, is forever imprinted on our minds. Gregor’s attempt, as brief and pathetic as it was, to move through his shame, becomes heroic for us as readers, as was the writing of the novella itself. Even though it was not successful, what mattered was that he tried. So, too, we must try, even if it is just one small step. Gregor shows us what is possible as a beginning, as an act of courage. It is up to us to see how ours will end. But we must move forward, with whatever agency has been left us, when all else has been taken away. As Kierkegaard wrote, “Continually take that one step more, that single step that even you, who cannot move a limb, are still able to take.”

Just as Gregor sacrifices himself for the sake of his family being able to restore equilibrium, so too did Kafka sacrifice himself as a writer for us as readers. He was engaged but never married, and ended up in a sanatorium. It was as if he suffered the loneliness, separation, and unresolved trauma deliberately, preserving it in a way, so that he could heroically take the axe to his own chest through writing, a tool too heavy and sharp to be successful for himself, rather than the soft and gentle hand of love.

.jpg)