Lenny Abrahamson’s film Room held me completely captive for its first hour, then left me stranded on the side of the road in its second. The film is an adaptation of the novel by Emma Donaghue, and towards the end I found myself almost losing interest, the magnetic pull having weakened, and thinking back to the magical time Jack (Jacob Tremblay) spent in seclusion with his mother, “Ma” (Brie Larson). Just then, as if the film had read my mind, Jack and Ma returned to the Room, at the request of Jack, so that he may bid farewell to each of the objects there, which he calls by name as if they were intimate friends–which, of course, they were: “Good-bye Lamp, good-bye Table.” My wish had been granted. But it was bitter-sweet. The return to Room was short-lived, a mere homage to a place that held such significance, especially for Jack.

Jack is molded by his time spent in Room, and although life outside Room is wildly infinite in its offerings, he seems to adapt quickly to this new reality and longs to return from whence he came. Jack’s “Room,” over time, begins to resemble the womb, and even Plato’s cave. His emergence, rolled up like a cigar inside a rug, is just as dramatic as a fetus being born (Jack’s disguise as being dead enables him to escape from the room). It is his first time outside Room, and when we see Jack see a sunlight-filled blue sky for the first time, it is one of the most exceptional cinematic moments in the last decade of film. Everything has carefully and strategically built up to this moment, and it is followed by a powerful and emotional reunion with Jack and Ma. It is exactly one hour of exceptional film, with a beginning, middle, and end. Where to go from here? The first half of the film is so strong that the second half feels at times like an extended epilogue. It does not rob the film of its provocative and emotive power, however, and there are some interesting moments.

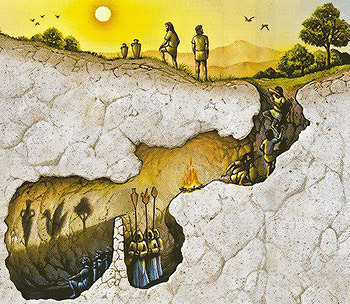

In Plato’s allegory of the cave, one of the prisoners chained inside is freed to explore the world outside the cave, wherein he had only been able to see shadows of what was real. His exploration of the world leads him a new reality that far outshines the one he experienced in the cave. He ultimately finds the Sun — the source of all living things. Upon returning to the cave, the prisoner has attempts to communicate to the other prisoners the things he has seen. They become hostile and resist his attempts to free them. Plato’s allegory says many things, but among the foremost of these is that man is both desperately curious about the Truth of things, yet at the same time does not want the responsibility of knowing those truths. He will seek, and he will reject what he finds. If he is a Truth-seeker, his is a lonely course. If he is a Truth-teller, others will reject what he says. Either way, this venture into the true nature of things is an exclusive and painful one.

So it is that Jack sees first, before anything else, the sky and the sunlight within that sky, a few umbilical-like telephone wires streaming overhead as he looks up from the bed of the moving pickup truck. The music is brilliantly understated and rhythmically, steadily calm, in a wonderfully restrained move by Abrahamson (I keep hearing the first explosive notes of The Cure’s “Plainsong” during this revelatory moment.) Jack’s eyes have been opened. He experiences a kind of second birth, a kind of enlightenment. Although circumstances have led Jack to experience the actual world in a delayed fashion by being secluded for his entire childhood up until this point, the moment itself is significant because of what it suggests for the average person: that we can wake up to reality in the same way if we just open our eyes. This is no different from the Buddhist idea of nirvana or Christ’s teaching that the kingdom of God is within you, and heaven is not a place, but an experience to be had here on Earth.

It’s also important to consider that Jack’s rebirth does not necessarily lead to joy or freedom. If anything, there is a recovery period followed by a painful integration into this new reality. A similar experience happens to the narrator at the end of Joyce’s wonderful short story “Araby.” Clarity of our existence is often a painful experience. It is the blissful blindness that comes with remaining in the darkness of the cave, of the womb, that we must let go of and come to mourn.